What I Wish I Knew When I Started Using Anki for Korean: Vocab Cards and Sentence Cards

Mini-series: What I Wish I Knew When I Started Using Anki In 2013 (language learning edition)

Should I Learn a Second Language?

3 Tools and 3 Tips for Learning a Second Language

Vocab Cards and Sentence Cards (You’re here!)

Mass Immersion

#1. Vocab cards (Don’t use it for abstract concepts!)

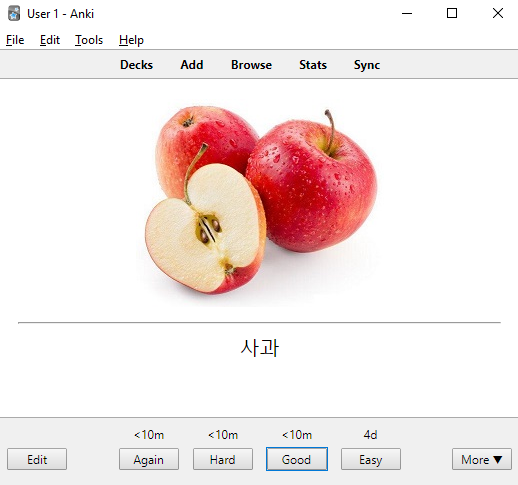

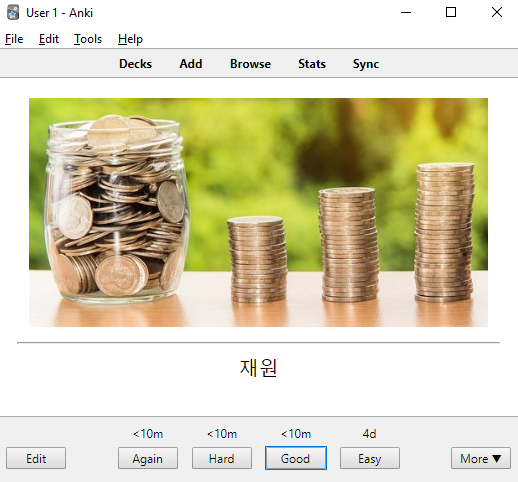

The front has an image to represent the vocab, then the vocab is shown at the back. This works well for concrete objects (apple, car, hand). However, for abstract ideas and nouns like freedom, finance, time, it’s difficult to find an image to represent the idea. Then with the ever-increasing intervals, it’s even harder to know what the image represents. So now you have two problems: encoding (finding an image to represent the vocab) and decoding (remember what vocab the image represents).

Decoding: remember what vocab the image represents

재원 means “source of money”, but the image can also represent 돈 (money), 금전 (another noun for money), 저축 (saving money), 재산 (asset) or even 동전 (coin). “This is obvious” if you have 10 cards, but with 2700 such cards and I bet you’re not so sure now.

I used to use images to represent abstract vocab like this. Most of my effort were figuring out what the image represents, not what the Korean vocab is for that thing (language representation). It was undesirable difficulty: spending effort on the wrong things (remembering that this image is about 재원 (source of money) but not 돈 (money), 금전 (another noun for money), 저축 (saving money) or 재산 (asset).

In other words, there are a lot of possible vocab for this image. Such ambiguity unnecessarily increases memory complexity and thus, doesn’t comply with Atomic memory. Using this card format dictates and forces you to remember the particular abstract vocab associated with a particular image. Memorizing what vocab this image represents is a huge waste of effort. It’s not relevant to vocabulary acquisition, but you’re spending a lot of mental effort answering this question: “What does this image represent?” 돈? 저축? 재산? Well they all mean “money…” With enough brute-force repetitions you can certainly do it, but I think it’s mostly wasted effort. In this case, “A picture is worth a thousand words” doesn’t work in your favor. I don’t recommend this. So what’s the solution? This brings me to:

#2. My sentence card implementation

Tying back to the above example, what image do you use to represent the concept “자주” (often)? For me, nothing comes to mind, like at all. However, with sentence card, I don’t have to.

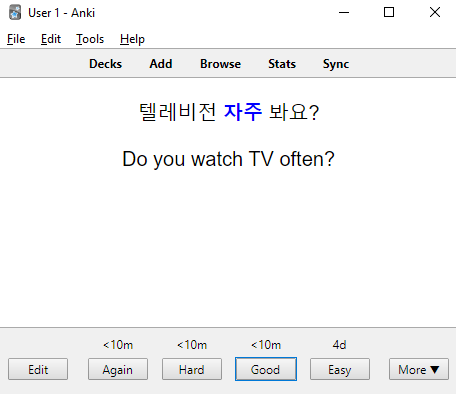

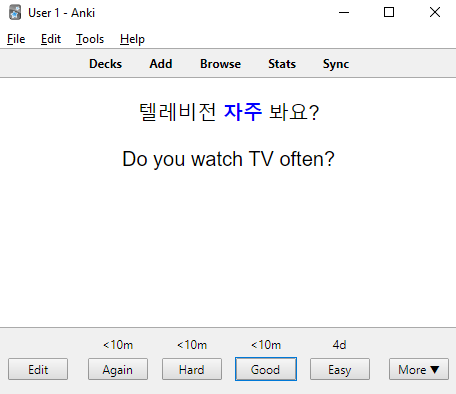

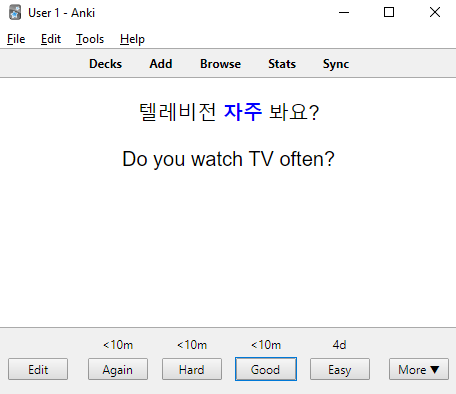

At the front, I have the Korean N+1 sentence “텔레비전 자주 봐요?” with the clozed “자주”. N+1 means that in a sentence, there’s only one vocab that you don’t know, hence being the target cloze. Then below is the English translation.

This sentence is easy for me to understand because I already know this sentence structure. It provides the natural usage (context) for the vocab “자주”. I like using a short sentence as one atomic unit. Long sentences obviously are too, well, long. Again, you need to take the sheer number of cards and reviews into consideration: the ability to realistically scale it to thousands of cards and potentially tens of thousands of reviews.

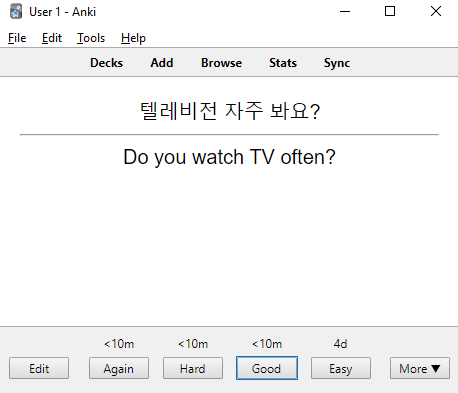

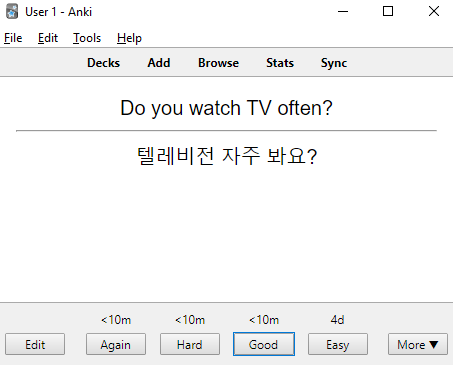

Two formats of sentence cards

I used to have these two formats of sentence cards:

- Vocab retrieval in a sentence:

- Sentence translation:

I choose “vocab retrieval in a sentence” (format 1) over “sentence translation” (format 2). First, “vocab retrieval in a sentence” has a clear-cut answer: either you remember the cloze or you don’t. With “sentence translation” however, it’s ambiguous due to not being atomic. In other words, in “텔레비전 자주 봐요?” there are three vocab and one sentence pattern. If you understand the sentence pattern but forget the meaning of “텔레비전”, do you press Good, Hard or Again? So the grading is ambiguous and easy to press “Good” because “2 for 3 is good enough.” In my experience, the more you do this the more you’ll unconsciously trick yourself that you understand the “meaning”, making you rapid-fire the reps without actually making an effort to understand it and discover what you don’t know.

There was, however, one advantage of “sentence translation” cards that prompted me to make them in the first place. Given the inherent versibility of the Korean language (just like any other language), with “sentence translation” cards you don’t have to care about the minor details. Just grade it “Good” if you understand the gist of the sentence. For example, there are many ways to express the same idea: “텔레비전 자주 봐요?”, “텔레비전를 자주 보십니까?” or “티비를 자주 봐요”, just different situations calling for different expressions. In this regard, I’d grade it “Good” if I can get the gist of that sentence’s meaning. I don’t have to get bogged down with the minor details: formal/informal expressions, honorifics, subject particles or any other language exceptions.

The other direction doesn’t work:

If it’s not obvious at this point, this format has too many possible answers. Every time your answer will probably be different, leading to endless unnecessary frustration

A brief explanation on sentence cards

Some people argue that you shouldn’t use L1 (first language) to learn L2 (second language). However, from Becoming Fluent:

Myth 3: When learning a foreign language, try not to use your first language.

Some adult language learners believe that they should never, ever, translate from their first language to their target foreign language. But this advice deprives adult language learners of one of their most important accomplishments—fluency in their native language. Although it is true that one language is not merely a direct translation of another, many aspects of one language are directly transferable to a second language. It’s not even possible to completely ignore these aspects, and trying to do so can be frustrating.

For example, an English-speaking adult who is learning Portuguese could hardly avoid noticing that the Portuguese word to describe something that causes harm in a gradual way, insidioso, is suspiciously like the English word insidious. It would make no sense to pretend as if prior language skill in English is not transferable in this case. It is true that such cognates are not found between all languages and are sometimes inaccurate (as in wrongly equating the English word rider to the French word rider, which means “to wrinkle”). Nonetheless, looking for places where concepts, categories, or patterns are transferable is of great benefit, and also points out another area where adult foreign language learners have an advantage over children.

The knowledge “stored” in your L1 can be helpful in helping you to learn L2:

Metalinguistic awareness refers to knowing about how your language works, and not just knowing a language. Metalinguistics is […] knowing how to use language to do things: how to be polite, or to lie, or to make a joke. In adulthood, metalinguistic knowledge can be impressively precise. Knowing the difference between a clever pun and a groan-inducing one, for example, reflects fairly sophisticated metalinguistic awareness.

The good news about metacognitive skills is that you don’t have to learn them all over again when you start learning a new language. Instead, you only need to take the metalinguistic, metamemory, and metacognitive abilities you’ve already developed in your native language and apply them to the study of your target language.

Language is arbitrary

PS: This is just my idea; take it with a grain of salt.

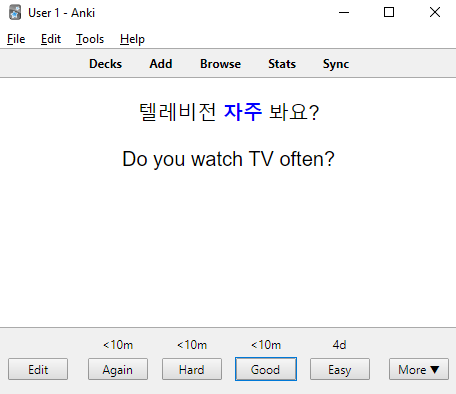

I don’t think it matters which language (L1 or L2) you’re using to represent and express your ideas. Again, take a look from this card. The input from L1 is for understanding the meaning of the sentence. Then with the meaning in mind, you try to construct and output the same meaning in L2:

Input –> Process –> Output

Do you watch TV often? —> Your brain —> Comprehension –> Your brain –> 텔레비전 자주 봐요?

In terms of meaning, there is no (major) difference between “텔레비전 자주 봐요?” and “Do you watch TV often?” The meaning is (largely) the same, just different representations (symbols, grammar patterns, pronunciation etc). And since you’ve spent decades honing your L1 to express millions of objects and concepts, why not take advantage of your massive prior knowledge in the form of L1 to aid comprehension and output in L2? I think the above sentence card formats can do this: You first read the sentence in L1 to get its meaning, then figure out how to represent it in L2. You already have what you need to work with: the sentence’s meaning. Your task is to figure out its representation in L2.

Input1: Do you watch TV often? —> Input2: Meaning of sentence in L1 –> Process: Your brain —> Output1: Meaning of sentence in L2 –> Output2: 텔레비전 자주 봐요?

When you’re learning a second language, the problem isn’t the meaning behind the vocab (abstract concepts such as freedom, finance, time) or sentence (i.e., “what does watching the television mean?"). If you don’t understand “텔레비전 자주 봐요?”, it’s either because:

I. vocab (텔레비전: television, 자주: often, 보다 -> 봐요 see)

II. grammar structure or pattern (in literal translation it’s: “Television often see?")

However, the fact that you can infer and derive the meaning from “Television often see?” indicates that understanding the meaning isn’t the problem. The problem is how to express them in L2: symbols (vocab), grammar patterns, pronunciation etc. So using L1 will take away this comprehension problem, leaving you more working memory to focus on the representation (e.g., how to express the same idea in L2).

Conclusion

Again, I’m not familiar with the current Anki/learning-a-second-language landscape. Make of it what you will. Regardless, I hope this article is useful.