Why I No Longer Tell My Friends about Anki/SuperMemo

Photo by Joshua Ness on Unsplash

Spreading the “gospel” to the world

If you deeply believe something, along the lines of “if everyone did it, the world would be much better off.” and have tried convincing other people to do that thing, then you will realize it’s almost impossible to change others' opinions or behaviors.

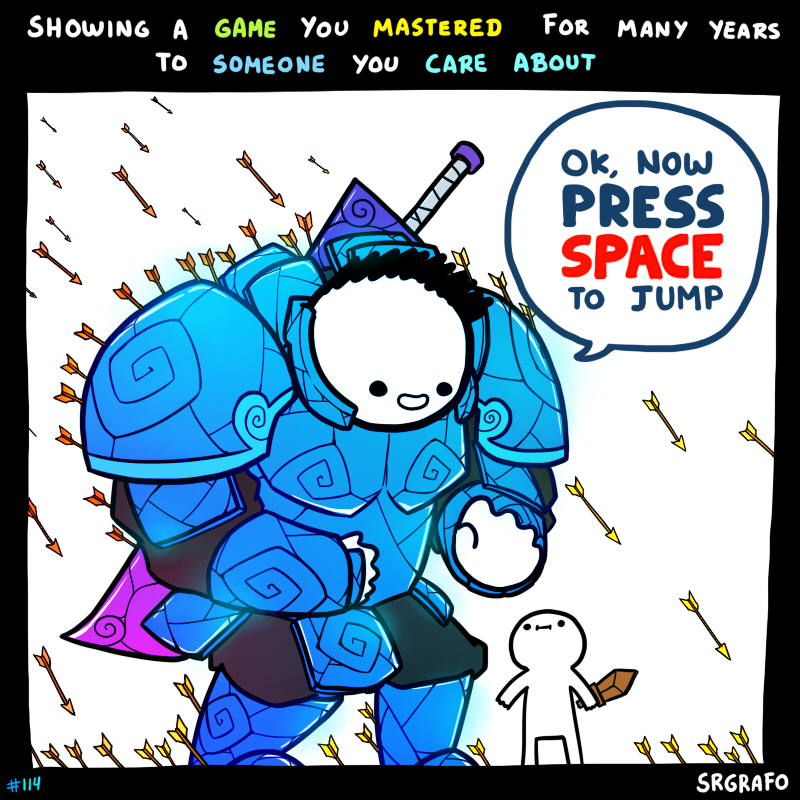

Maybe you’re not that ambitious to convince everyone, so you start small: you share it to your friends, but then discovered nobody actually cares or realizes its significance. A mild version is like showing your favorite TV show and they don’t care:

My faith in evidence-based learning strategies is informed by my personal experience and my meta-learning list. I wholeheartedly believe Spaced Repetition Software (SRS) like SuperMemo and Anki is the key to effective and efficient learning. If you believe education is the future, then the knowledge about evidence-based learning strategies is one big key to unlocking that future, both individually and collectively.

“Doing this every day seems very tiring.”

Two years ago I was doing my Anki reps. One friend glanced over and was interested in what I was doing.

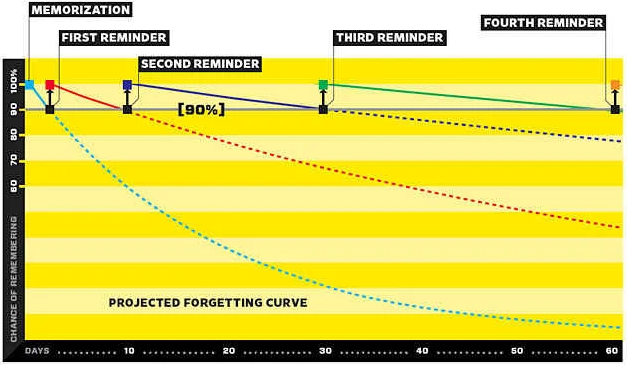

We had lunch together while I was giving her a little presentation. I talked very enthusiastically about spaced repetition, basic memory science and Anki operations. Of course I had to show her the infamous forgetting curve:

She sounded excited about the possibility of finally mastering a second language. But at one point she was confused:

“If I hadn’t learned it how could I recall it from memory?”

So I explained that assessment for learning (testing as a means of learning) is different from assessment of learning (finding out what you’ve learned). The act of “recalling from memory” is itself a learning process. Then I was aware that her confusion was probably due to a common misconception about memory, that human memory works like computer memory:

The functional architecture of how humans forget, remember, and learn is unlike the corresponding processes in man-made devices […] We think of ourselves as working like computers, we become prone to assuming that exposing ourselves to information and procedures will lead to storage (i.e., recording) of such information or procedures in our memories—that the information will write itself in one’s memory.

If we think of human memory equals to memory in a computer, we are unlikely to appreciate that retrieving information from our memory increases the subsequent accessibility of that information, while retrieving information from computer memory leaves the status of that information unperturbed. On the Symbiosis of Remembering, Forgetting, and Learning

She looked… befuddled. Sort of like this:

I remember I was so excited and nervous at the same time that I was fumbling for words, trying to simplify it as much as I could. In retrospect, I was making things worse.

She’d listen to me quite intently, signaling that she was thinking and trying to figure it out, but I could tell she was still confused. And the more I explained, the deeper the rabbit hole went (like keep clicking hyperlinks in Wikipedia), and the more confused she became, so I stopped talking to stop making the whole situation uncomfortable. The following monologue is how I imagine what she was thinking at the time:

“He’s so passionate about this stuff and so sure of himself that I guess he’s right.”

“I’m not really sure what he means. I do want to learn Japanese but the stuff he’s talking about is so confusing…”

“I was indeed interested in the beginning, but I don’t really care at this point. I’m just going to pretend I understand and end this whole conversation asap.”

I would never forget what she said at one point,

“Doing this every day seems very tiring.”

I was like “Yeah…” I never followed up on her progress. I figured if she was truly interested, when she bumped into problems she would ask for my help. As expected, we never talked about it and I never mentioned Anki again.

These has happened countless times. I usually look nonchalant on the outside but dying on the inside. People looked interested (probably due to my enthusiasm and it’s impolite to look otherwise) and then never actually bothered to use Anki. Some would actually try, make a few cards, do the reps for a few days and then say, “I tried and Anki doesn’t work.”

I’m probably over my head, but sometimes it feels like I’m personally attacked, that what I’m saying is not valuable. I understand it’s not true, but it took me years to study the learning science and to gain the experience with Anki/SuperMemo. The fact that they’re dismissing the software feels like they’re dismissing my knowledge and experience.

The problems with giving advice on how to learn

#1. Nobody cares that much, alright?

When I first discovered Anki I was like, “How come no one around me knows this?! I need to share this to everyone!” So I would tell my friends about Anki but nobody was interested. I’ve introduced Anki to people and every time it’s a very frustrating experience. (Surprise surprise, not SuperMemo. The learning curve of Anki is much lower. What chance do I have if I preached SuperMemo when they even think Anki is too hard to use?)

Update: I was never a missionary and randomly went out my way to tell people about Anki all the time like this:

Very early on I did give unsolicited advice once to my best friend by intentionally bringing up Anki. Then I did bring up Anki on multiple occasions, but only when the opportunity presented itself, like the story above.

People may be interested in how you’ve developed a skill or become fluent in a foreign language, but just aren’t that interested. And they certainly don’t expect to be suddenly lectured on how learning and memory work.

I never liked following up to people with questions like “So how’s Anki? Have you used it?” It feels like pushing an agenda to them. Also, since most would not even bother buying and downloading the app, their response is usually, “I forgot about it. I’ll do it later.” and the conversation would end in an awkward tone.

#2. I’m not sure if I actually want it, alright?

Sometimes people keep lamenting “I want to learn X or I want to get better grades.” How many times do you hear people say they want to learn a second language? This is like that friend who keeps saying “I want to lose weight”. Probably after all, they’re just lamenting and not yet ready to put in the effort to change.

Trying to convince others to use Anki/SuperMemo is like trying to convince your friends to go to the gym regularly. You can talk about the benefits of exercising/weight-lifting, how good you’ll feel afterwards, how much more productive you’ll be and so on. But nothing will work if they don’t try it in the first place, and it doesn’t help that spaced repetition doesn’t work in the short-term since using Spaced Repetition Software is a life-long pursuit (just as learning is):

This long term focus may explain why explicit spaced repetition is an uncommon studying technique: the pay-off is distant & counterintuitive, the cost of self-control near & vivid. Gwern’s Spaced Repetition for Efficient Learning

#3. Why are you so hyped about it?

It’s rare if people could understand and realize the significance and application of Spaced Repetition Software in a casual 10-minute chat. It’s not about its complexity (it’s not rocket science after all), but rather it’s about awareness: problems with current learning approaches and how Anki/SuperMemo could solve the problems. In other words, if I don’t see the problems, why bother changing?

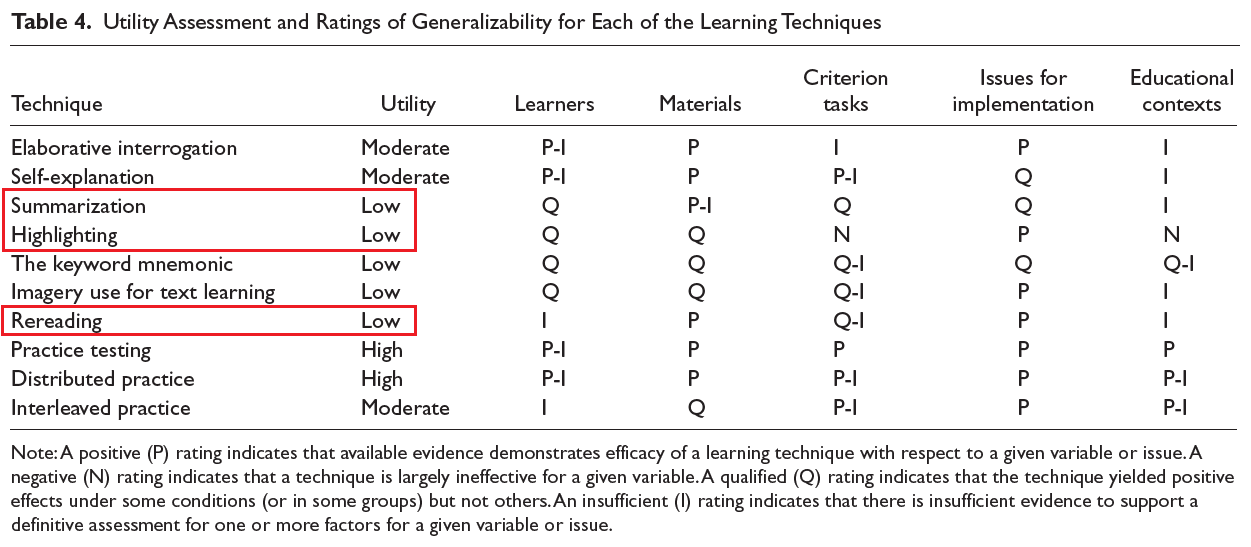

I have a friend who was learning German. She copied German vocabulary on one side and the equivalent English on the other in a notebook. I showed her my Korean Anki cards: “Take a look at these beautiful images! Gifs! Sentence cards! Audio clips! Mass Immersion Approach! (Former: All Japanese All The Time (AJATT)), Stephen Krashen’s Input Hypothesis!” Then I had another friend who was studying to become a nurse. I told him about Anki: “Image occlusion for anatomy!” It felt wrong of me to be hiding Anki (Image Occlusion to be specific) from him. Deep down I want to shove their faces to this table:

(Image source: Improving Students' Learning With Effective Learning Techniques)

I was exaggerating but you get the point: it’s not possible to convey the significance and application of it all in a casual 10-min chat. With the benefit of hindsight, all my attempts could’ve been a lot better:

-

Maybe I was so convinced and have so much faith in Spaced Repetition Software that I came off as condescending, giving off the impression like “you don’t know how to study; let me teach you.”

-

Maybe it’s the bold claims: “You’ll get 2x results with half the study time.” (How many are really true whenever you hear such claim?)

-

Maybe it’s the situation: all he or she wants is someone to listen about the difficulty of studying, not some real advice or suggestions.

Here’s the guy from How I Passed the Demanding […] Italian Language Exam Without Going to Italy – Here’s a Hint: the 326,538 Flashcard Reviews Helped a Lot.

Like many language teachers, V. had never heard of Anki (but she did know Reverso Context). I showed her how I studied Italian vocabulary, and some Japanese as well. To her credit, she did download the software and a few decks to try out herself. I’m fairly certain she stopped two days after I left. She claimed conversation is the most important thing for learning a language. While I agree in some aspects, there’s no way conversation can cover all the vocabulary in a language.

#4. Your friends need to experience the magic of Anki/SuperMemo themselves

This point is corollary to the above: your friends don’t understand your hype because they haven’t experience the magic of Anki/SuperMemo themselves. Even Michael Nielsen had trouble sticking with Anki. As mentioned in Augmenting Long-term Memory:

I had trouble getting started with Anki. Several acquaintances highly recommended it (or similar systems), and over the years I made multiple attempts to use it, each time quickly giving up. In retrospect, there are substantial barriers to get over if you want to make it a habit.

What made Anki finally “take” for me, turning it into a habit, was a project I took on as a joke. I’d been frustrated for years at never really learning the Unix command line. I’d only ever learned the most basic commands. Learning the command line is a superpower for people who program, so it seemed highly desirable to know well. So, for fun, I wondered if it might be possible to use Anki to essentially completely memorize a (short) book about the Unix command line.

It was!

I chose O’Reilly Media’s “Macintosh Terminal Pocket Guide”, by Daniel Barrett. I don’t mean I literally memorized the entire text of the book. But I did memorize much of the conceptual knowledge in the book, as well as the names, syntax, and options for most of the commands in the book. The exceptions were things I had no frame of reference to imagine using. But I did memorize most things I could imagine using. In the end I covered perhaps 60 to 70 percent of the book, skipping or skimming pieces that didn’t seem relevant to me. Still, my knowledge of the command line increased enormously.

Choosing this rather ludicrous, albeit extremely useful, goal gave me a great deal of confidence in Anki. It was exciting, making it obvious that Anki would make it easy to learn things that would formerly have been quite tedious and difficult for me to learn. This confidence, in turn, made it much easier to build an Anki habit.

This goes the same with SuperMemo’s Incremental Reading, Org mode in Emacs, Vim, Obsidian, Roam Research, Arch Linux, or using SSD over HDD: your friends need to experience the magic themselves in order to be convinced. This reminds me of this AskReddit post: What life changing item can you buy for less than $100?. When you look at the comments, you’ll surely be confused:

How can a curved shower rod be life-changing?

King-sized blanket? Sharp knives fo the kitchen? Weighted blanket? Vertical mouse? Life changing?

You don’t think they are life-changing because they didn’t change your life, but it did change the commenter’s life. Or even more generally, you may not understand why your friends are excited about a new gardening technique, find embroidery fun, ASMR relaxing, or trains fascinating. This goes the same with Anki/SuperMemo. If Anki/SuperMemo had pulled his/her grades by orders of magnitude, no convincing is needed.

How a typical 15-min conversation goes

Say, your friend has the generosity and is willing to listen to you babble about Anki for 15 minutes.

1. 5 minutes on the problems with current approaches (re-reading/copying verbatim notes)

2. 5 minutes on the superiority of spaced repetition. This is where you’d show off the forgetting curve and how Anki addresses forgetting.

3. 5 minutes on basic Anki operations: how to grade a card and how to make cards with the two basic card types (clozes and Q&A)

In my experience 15 minutes is not enough, or rather, no amount will be enough. Persuasion is an art in itself. I told people about Anki purely out of altruism. I soon realized it was causing me more frustration than it’s worth, and so I’d let it slide.

The problem with faulty intuitions and biases (about learning) is that they are notoriously difficult to correct. Understanding How We Learn: A Visual Guide

I’m not immune to cognitive biases

I don’t usually follow people’s recommendations and advice myself. People sometimes talk and share something they’re passionate about with me. I’m like, “Ok… so…?” Do I follow their advice? Not likely. Do I do that thing they preached? Usually not. So I understand when I was treated the same when I was spreading the gospel of Anki to everyone. A taste of my own medicine indeed. What I want to say is, it’s difficult for anyone to change opinions. If you tell me SuperMemo/Anki is a piece of sh*t I would simply flip out.

Conclusion

Should you stop recommending Anki/SuperMemo to a friend? I don’t know you and your friends so I can’t make any generalization. So what’s the takeaway? If you tell your friends about Anki/SuperMemo, don’t be too enthusiastic (on the outside) or else you’re going to scare them off (Source):

This is one reason why I started this blog: if people realize the value of what I’m saying, they would be naturally attracted to my content, so I’ve decided to share what I know online. Maybe some will bump into my site; then a subset will get interested and actually give it a shot; then another subset will discover the joy of learning and experience the true power of SRS.

If you want to know more, check out my article Why 99% People Never Learned How To Learn And How to Become That 1% (I) and (II).