Why SuperMemo/Anki is More Than a Memorization Tool (1) Introduction

This is a 4-part series:

(1): Introduction (2): Prior Knowledge (3): Transfer of Knowledge (4): Higher-order Thinking

In this first article, I’m addressing some of the stigma associated with memory, memorization and testing.

Series Introduction

This series will for sure provoke some feelings: either positive because you agree with me (cognitive ease) or negative because you don’t (cognitive dissonance). For the latter case, hats off for enduring the cognitive dissonance and at least willing to entertain the title and potential any upcoming content.

Everyone has his/her own implicit (unconscious) ideas about how to learn (best), since we all have spent so much time in school. We all bring different ideas to the table. The term memorization may even provoke dread, hatred, or fear depending on your learning experience. I don’t know who you are and can only make some broad generalizations about what concepts and associated ideas you might have when seeing words like “learning”, “understanding”, “remembering”, “memorizing”, “prior knowledge”, “school” etc.

Umbrella terms with their associations can spread like wildfire. For example, your initial association with “testing” might be “standardized testing”, but “testing effect” or “low-stakes testing” are two extremely related concepts that most would not think of. Personally, the word “memorizing” will provoke more negative connotations than “remembering”, as “remembering” somehow is more neutral than “memorizing”.

It’s more about un-learning than learning.

The stigma associated with these umbrella terms is a hindrance towards understanding the learning science. However, if you want to take your learning/studying game to new levels, then you have to be willing to distance yourself from these negative associations.

Take my words with a grain of salt

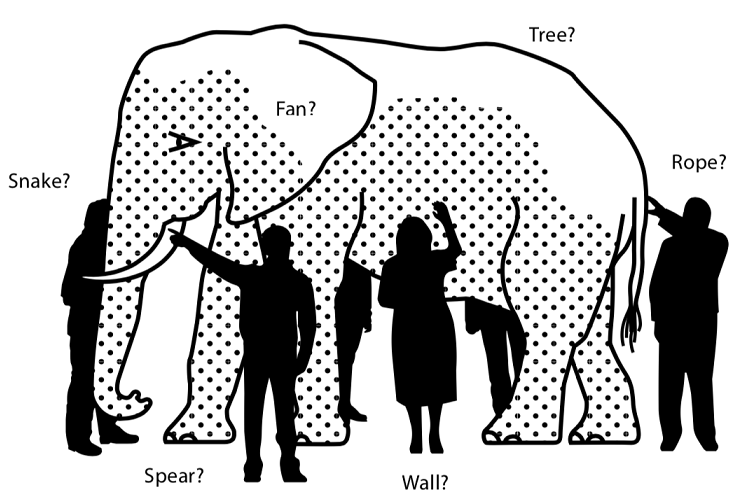

I have my own cognitive biases and learning experience that has led me to believe what I believe now. It’s not possible to capture and unearth my entire meta-learning knowledge and beliefs in one series. For example, when I think of memorization, I also think of prior knowledge, transfer of knowledge, or metacognition, each of which have entire books dedicating to just one concept. It’s hard to isolate one aspect to explain the whole: you can’t understand the elephant just by touching her trunk. Blind Men and the Elephant:

Besides, it’s not easy to untangle a web of concepts, connect and address different facets of such a broad subject (also because I’m no writer). And to be honest, I have neither the expertise nor the time to synthesize such a broad knowledge in my spare time.

Given the above reasons, take everything here with a grain of salt. Better yet, pick a few books from How to Learn About Meta-Learning: My Resource List or A 4-Step Roadmap Towards the Mastery of How to Learn to understand the science of how to learn. I could never do this topic justice better than those authors. If you are serious about learning how to learn, devour the books from the list and beyond.

In this series, I’m mostly citing different sources to support my arguments because well, they add weight and are more credible than some random blogger.

The Stigma Surrounding Testing and Memorization

These claims are common:

“SuperMemo/Anki is only for remembering, not learning.”

“You need to understand before memorizing with Anki.”

“You don’t need to memorize; you only need to understand concepts/proofs/application.”

The following (I didn’t make it up) online comment sums up nicely about most people’s aversion and misunderstanding towards memorization:

“You shouldn’t try to learn [insert your subject of interest here] through memorization at all. It will get you nowhere: anything that can be memorized can be looked up these days. What you should try to learn is the underlying concepts and the way they relate to each other. If you understand those well enough, you won’t need to memorize anything.”

How bad is the stigma against memorization and memory?

“I don’t use the word ‘memory’ in my class because it’s a bad word in education,” says Matthews. “You make monkeys memorize, whereas education is the ability to retrieve information at will and analyze it. But you can’t have higher-level learning—you can’t analyze—without retrieving information.” And you can’t retrieve information without putting the information in there in the first place. The dichotomy between “learning” and “memorizing” is false, Matthews contends. You can’t learn without memorizing, and if done right, you can’t memorize without learning. - Moonwalking with Einstein

Testing is likely viewed by many students as an undesirable necessity of education, and we suspect that most students would prefer to take as few tests as possible. This view of testing is understandable, given that most students' experience with testing involves high-stakes summative assessments that are administered to evaluate learning. This view of testing is also unfortunate, because it overshadows the fact that testing also improves learning. - Improve Students Learning With Effective Learning Techniques

It’s the case that since testing invokes so many negative connotations that researchers had changed the from “testing” to “retrieval practice” to avoid the stigma. As explained in How We Learn:

The word “testing” is loaded, in ways that have nothing to do with learning science. Educators and experts have debated the value of standardized testing for decades, and increasing the use of such exams—only inflamed the argument. Many teachers complain of having to “teach to the test,” limiting their ability to fully explore subjects with their students. Others attack such tests as incomplete measures of learning, blind to all varieties of creative thinking. This debate, though unrelated to work like Karpicke and Roediger’s, has effectively prevented their findings and those of others from being applied in classrooms as part of standard curricula. “When teachers hear the word ‘testing,' because of all the negative connotations, all this baggage, they say, ‘We don’t need more tests, we need less,' " Robert Bjork, the UCLA psychologist, told me. In part to soften this resistance, researchers have begun to call testing “retrieval practice.”

Typical associations with memorizing and testing

If your ideas about memorization are students sitting in a classroom parroting back after the teacher, or when you think of “testing”, you immediately conjure up the painful memory of stressing over a big exam: having to scribble a few more words moments before hearing “TIME’S UP PENS DOWN”:

No worries. I’ve experienced them all. Your ideas have more to do with schools (education systems) rather than the learning science. I went through 15 years of formal schooling, from kindergarten to college, so I have first-hand experience in both sides. This is not what I have in mind when I talk about testing and memorizing.

Testing is not the same as Standardized Testing

Retrieval practice (testing) is a learning strategy, not an assessment strategy. Retrieval practice is not a call for more testing; it’s the opposite. Retrieval practice is successful when we foster learning in a supportive, no-stakes environment. Power Teaching

Our rationale for focusing on [generative learning] is that the twenty-first century needs problem solvers and sense makers. The need for rote learning and associative learning is somewhat reduced because we now have access to databases that can store vast amounts of information or give answers to simple questions. The world needs people who can select, interpret, and use information to solve new problems they have not encountered before. Learning as a Generative Activity

These descriptions appeal to everyone. I’d be nodding my head if someone says it on stage. You might think it’s a call for less testing. So what are the solutions provided from the book? No spoiler alert: here are the eight generative learning strategies that promote learning: Summarizing, Mapping, Drawing, Imagining, Self-Testing, Self-Explaining, Teaching and Enacting.

Self-testing is a big toolkit in achieving “twenty-first-century skills such as creative problem solving, critical thinking, adaptability, and complex communication.” Spaced Repetition Software (SRS) such as SuperMemo and Anki is the direct way to do self-testing (self-testing is not the same as rote learning or memorizing verbatim):

Self-testing involves answering practice questions about previously studied material to enhance long-term learning. For example, after reading a chapter in a textbook, a student answers practice questions on the material without referring back to the chapter. In 44 out of 47 experimental tests, students who studied material and then took a practice test performed better on a later test than students who only studied the material (median d = 0.62). Further, in 26 of 29 additional comparisons, self-testing was more effective than restudying or otherwise receiving extended study time (median d = 0.43).

Asking students to self-test allows students to practice accessing previously learned material from long-term memory (i.e., engage in retrieval practice), which may facilitate the processes of organizing and integrating the material with their existing knowledge, resulting in enhanced long-term memory.

Two important implications for the testing effect: (1) practice testing may need to be coupled with corrective feedback; and (2) more generative practice tests (such as free-recall rather than recognition) may lead to the best long-term learning. Learning as a Generative Activity

Note that the author used the phrase “long-term learning”, not merely “long-term memory”, suggesting that self-testing is more than just leading to better long-term memory. Surprise, surprise. So in order to achieve the above learning objectives, one has to test oneself. Briefly, you can’t have meaningful learning without retention:

Generative learning is indicated when someone performs well on retention and transfer, that is, the learner can both remember and use what he or she has learned to solve new problems.

Spaced Repetition Software (SuperMemo/Anki) is the best way to do self-testing

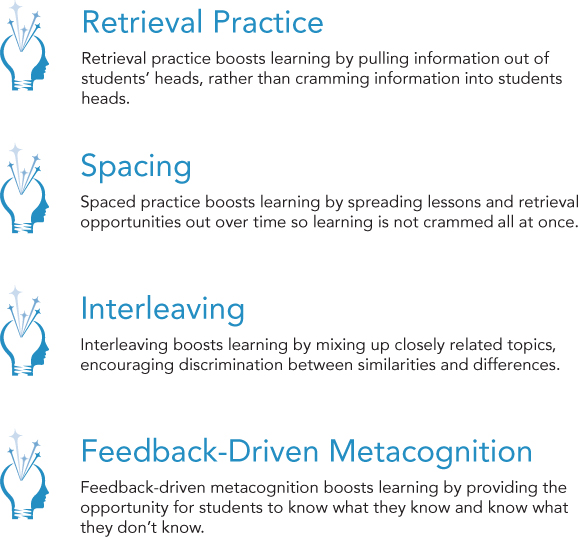

SuperMemo/Anki is the implementation for retrieval practice, spacing, interleaving and feedback-driven metacognition (illustration from Powerful Teaching):

Any SRS has all of the above 4 “Power Tools”:

Retrieval practice: recall the answer for an Item (SuperMemo) / a card (Anki).

Spacing: Ever-increasing intervals for each successful recall

Interleaving: This is the default in SuperMemo. In Anki it’s by decks. This is what I called micro-interleaving vs macro-interleaving(../2018-10-30-the-significance-of-incremental-reading-part-ii/)

Feedback-driven metacognition: you immediately know whether you could recall something to mind and then check against the answer.

Power tools improve more than memorization

“Do these strategies (4 Power Tools mentioned above) improve more than just memorization?” Here’s our answer, based on years of cognitive science research and classroom practice: Yes!

These four Power Tools improve students' higher-order learning, ranging from a deep understanding of mitosis to effectively resuscitating someone using CPR. As educators, we know that boosting learning beyond the memorization of facts is critical. And that’s why we advocate for the use of these strategies – because decades of research demonstrates that they improve much more than just memorization. We share specific research studies and teaching tips to emphasize that retrieval practice, spacing, interleaving, and feedback-driven metacognition boost students' basic understanding of information, and students' higher-order learning and transfer of knowledge, too.

My faith in SuperMemo/Anki is based on my faith in the literature of evidence-based learning strategies such as spacing effect, retrieval practice and interleaved practice. SRS is the tool to implement these learning strategies.

Of course, one has to be careful about interpreting and translating the results from research. How big of a leap of faith depends on your judgements and interpretation. More importantly, how you wield the SRS will determine how effective it is:

“Having the right tools is only one part of the equation. It is easy to get fooled by their simplicity. Many “tried them out” without really understanding how to work with them and were disappointed with the results. Tools are only as good as your ability to work with them.” - Dr. Sönke Ahrens How to Take Smart Notes

Regardless, you’re missing out if you avoid memorizing like a plague or see SRS as the tool to just remember factoids:

While Anki is an extremely simple program, it’s possible to develop virtuoso skill using Anki, a skill aimed at understanding complex material in depth, not just memorizing simple facts. Augmenting Long-term Memory by Michael Nielsen

Conclusion

I think it’s better to address some ideas you may have before proceeding because I want to prime you to be more receptive to the upcoming content. If I’ve made you more at ease about memorization and testing in general, , then I’ve done my job. Hopefully I’ve piqued your interest enough that you’d go read How to Learn About Meta-Learning: My Resource List.