Why 99% People Never Learned How To Learn And How to Become That 1% (I)

Photo by Philippe Bout on Unsplash

-

We did not learn how to learn in school, so we simply don’t know how

-

Difficult to uproot established but wrong learning ideas

-

Old learning habits die hard

-

Old mentalities die hard

1. We did not learn how to learn in school, so we simply don’t know how

Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning:

Learning is an acquired skill, and the most effective strategies are often counterintuitive.

For the most part, we are going about learning in the wrong ways, and we are giving poor advice to those who are coming up behind us. A great deal of what we think we know about how to learn is taken on faith and based on intuition but does not hold up under empirical research.

Persistent illusions of knowing lead us to labor at unproductive strategies; this is true even of people who have participated in empirical studies and seen the evidence for themselves, firsthand.

On the Difficulty of Mending Metacognitive Illusions:

Every school curricula focuses on the content, i.e., what you need to learn or know by a certain age, not how you acquire it. I never learned how to learn in school and had to read on my own (How to Learn About Meta-Learning: My Resource List). This reminds me of allegory of the long spoons:

In terms of meta-learning, the food is the learning resources and you’re alone with a long spoon. Without first learning how to learn is like trying to eat with that long spoon. It won’t work, or at the very least, not effective and efficient.

This is a great tragedy because everyone spends so much time in school and pays so much for school. Also because there are wonderful high-quality learning resources (free or otherwise) all over the Internet. The problem is never any lack of resources; it’s how to consume them.

Without first learning how to learn and dive straight into it will only result “in one ear and out the other”, like pouring water into a leaky bucket: you keep pouring (time and effort) and the bucket just keeps leaking.

Studying methods are just like everything else: there are always better and worse ways to do it (think about opportunity cost): (re-)reading the textbook, googling supplementary articles, studying with friends, writing notes, creating flashcards, etc. Since “how you study” also means “how you spend your time,” I think it’s a terrible waste of time and effort without first knowing how to learn.

As I’ve written before Hypothetical Situations: Should I Use Anki, SuperMemo or Both?, you don’t even need Anki for college, let alone SuperMemo (although either of them will make your academic life dramatically easier). Once you’re done with school (mostly synonymous with education and learning), you don’t have strong impetus to keep learning, not to mention improving your learning methods.

2. Difficult to Uproot Established But Wrong Learning Ideas

I. Established Ideas

Once an idea has taken root in your mind you’re not going to change it easily. When something contradicts with what you believe it’s cognitive dissonance. PS: I’m not excluding myself: It was hard for me when switching to Vim’s modal typing. It has completely changed the way I type and write (but that’s a story for another time).

When I say “testing works,” you’ll most likely to have various negative connotations towards it because it’s the polar opposite of the general consensus:

“Testing is a thing of the past. We don’t need to produce more rote memorization robots but creative and analytical thinkers!”

“Testing is useless; it’s just rote memorization.”

“What do you mean testing is learning? It’s assessment: testing what I know.”

“Tests are stressful.”

These were my past beliefs so I understand them, particularly the last sentiment because I was a victim myself. Who would want to relive such traumatizing experience:

Most people associate testing (retrieval practice) with a host of other things (examinations, rote memorization, assessments). When your ideas about testing are the norms: High-stakes (“pass-or-die”) and its sole purpose is assessments, you’ll get confused when I say “testing works”, in which I actually mean no-stakes and self-administered flashcards.

This is highly unfortunate. Direct experience always beats empirical evidence: If you have bad past experience with school/testing/memorization, negative connotations simply carry on forever, and you’ll miss one of the most potent learning methods available.

II. Wrong ideas: what work are the exact opposite of what most people think

A: “Testing works!"

B: “Testing doesn’t work!"

A: “Cramming doesn’t work!"

B: “Cramming works!"

A: “Practice-practice-practice(*) doesn’t work!"

B: “Practice-practice-practice works!"

What your intuition tells you to do: Intuition persuades us to dedicate stretches of time to single-minded, repetitive practice of something we want to master, the massed “practice-practice-practice” regime we have been led to believe is essential for building mastery of a skill or learning new knowledge.

These intuitions are compelling and hard to distrust for two reasons. First, as we practice a thing over and over we often see our performance improving, which serves as a powerful reinforcement of this strategy. Second, we fail to see that the gains made during single-minded repetitive practice come from short-term memory and quickly fade. Our failure to perceive how quickly the gains fade leaves us with the impression that massed practice is productive.

If what I’m suggesting is not the direct opposite, but some other ideas like “learning styles works,” people will not object so vehemently. For some reason (possibly marketing), the norms are to favor learning styles: “Learning styles may work but testing definitely doesn’t work.” I’ve seen companies selling expensive services that test whether you’re a visual or auditory learner. But unfortunately, the idea of learning styles is an unsubstantial claim:

The popular notion that you learn better when you receive instruction in a form consistent with your preferred learning style, for example as an auditory or visual learner, is not supported by the empirical research. (Make It Stick)

[T]he experimental literature on learning styles is poor and the existing evidence mixed that there are such things as learning styles. (Gwern’s Spaced Repetition for Efficient Learning)

Therefore, most have the wrong ideas about what works and what doesn’t work. One needs to clear out roadblocks after roadblocks before succeeding in learning how to learn:

- Understand why existing methods like re-reading, merely taking notes don’t work (or else why do I need to change?)

- What actually works (retrieval practice, spaced repetition, interleaved practice) and why they work (testing effect, interleaving effect, desirable difficulty)

- Remove negative ideas about testing. If one is particular vehement about testing or memorization, he or she needs to be open enough to entertain the idea that it is exactly “what I think doesn’t work” that actually works.

- Persist despite a host of cognitive biases and intuitions about learning (illusion of knowing, perceptual fluency, stability bias) See also: If SuperMemo/Anki Really is THE BEST Learning Tool, Why Isn’t Every Student Using It?

My point is, once an idea about learning is lodged in someone’s mind, he or she is not going to change easily (if at all).

3. Old Learning Habits Die Hard

Becoming Fluent: How Cognitive Science Can Help Adults Learn a Foreign Language:

Doing what you’ve always been doing is immensely easier than coming up with new ways to learn. Take note-taking as an example:

1. “Write better notes”: using shorthand like i.e., e.g.

2. “Learn new ways to take notes”: lead you to the Cornell note-taking method

3. “Learn new ways to study”: abandoning taking notes altogether and start using SRS (Spaced Repetition Software)

#1. It doesn’t deviate much from what you’ve always been doing. It’s a small change and you know what to do.

#2. It requires quite a substantial change to how you approach taking notes, but still, it’s note-taking.

#3. Completely replacing one activity with another is unlikely. “What to replace it with?" Such radical change is unlikely unless you have a predetermined destination (i.e, replacing note-taking with flashcards)

Given the preconceived notion of studying is “sit down with a book and notebook. Then start taking notes and highlighting”, when thinking of “improving my studying”, most would think of “I need to write better notes” over “I need to learn new ways to take notes”, not to mention “I need new ways to study.”

4. Old Mentalities Die Hard

I. Fixed Mindset:

“Yeah I don’t remember a lot of things. What can you do about it?

“I’m naturally and genetically born with bad memory.”

“No matter how hard I try I just can’t improve.”

The assumption is that there’s nothing you can do about it: “It is just the way it is.” Obviously these are not true but these beliefs can really prevent you from exploring how to learn.

II. You Don’t Need to Learn How To Learn; Just Study/Work Harder

Your experience from failing an exam is likely to lead to “I need to work harder, study longer so I don’t forget and fail my exams again.” Doubling down your effort is the most straightforward solution, with the assumption that “working” harder means better results and memory.

Completely restructuring how you study is much harder than doing the same thing with higher intensity.

Structural change: What do I do then?

Higher intensity: Instead of studying for two hours I’m going for four.

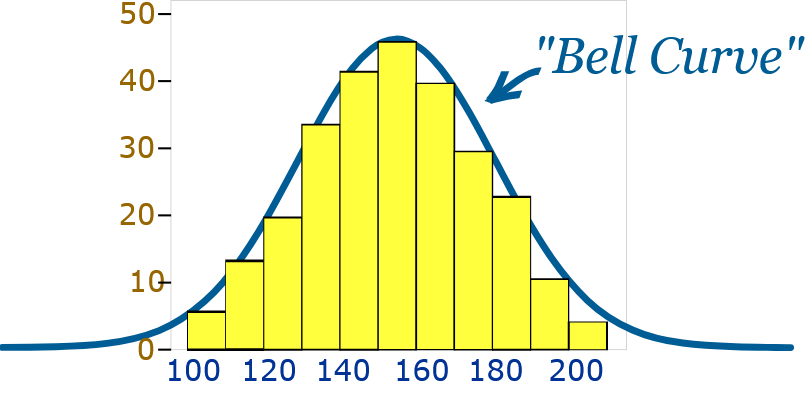

There’s limit on how much more time you can put into before hitting the ceiling. Like a bell curve: you’ll hit negative returns very quickly. You need to undergo qualitative (structural) change, not quantitative (more time) change.

Throughout my high school years, it never occured to me that I needed to change my study methods. If I scored low or failed a test it was because I wasn’t working hard enough, so it never occurred to me that I needed to change anything.

What I thought was working wasn’t really working. I’d never developed the right ways to learn and study; I’d internalized the wrong approach and mindset (more time re-reading = higher scores). But hey, if it ain’t broke… Ultimately, when the college entrance exam came, everything felt apart and it was already too late. Before the real exam, results from my practice tests were highly undesirable. So I doubled down the effort: I spent more time re-reading my textbooks, more time copying verbatim, basically more time exposing myself to the learning material (Misconception About Memory: Human Memory is NOT Like Computer Memory). The result? Not much improvement. I doubled down my effort but it yielded very little improvement. It was devastating. The feeling of helplessness and hopelessness can really destroy you if you felt like the exam determined your future. I was Boxer the horse from Animal Farm:

So How Do You Become That 1%?

1. How to Learn About Meta-Learning: My Resource List

2. A 4-Step Roadmap Towards the Mastery of How to Learn (6 Years of Experience Summarized

TL;DR: Just use SuperMemo/Anki

Do I Really Mean That 99% Do Not Know How to Learn?

Who are you to be making such egotistical claims?

In my opinion, the answer is a resounding yes. “99% people do not know how to learn” is not just a bold claim; it’s the sad reality. More specifically, I refer to not knowing how to learn effectively and efficiently. Re-reading your textbook and writing the foreign language in one column and your native language in another are indeed learning… just not effective.

Given there are over one billion students worldwide, 1% means ten millions and I’m very sure there are no ten million Anki/SuperMemo/Mnemosyne/plus all other Spaced Repetition System users.

[i]t seems fair to […] conclude that the worldwide population is somewhere around (but probably under) 100,000. Gwern’s Spaced Repetition for Efficient Learning

r/Anki currently has 25k learners; r/Medical School Anki 38k; r/super_memo and r/superMemo combined with a few hundred members; The official Anki forum; Mnemosyne’s community has around 1k member. All of them account for less than 1%.

Dare I say, those who know how to learn are those high-school valedictorians, medical or law school students, which surely all belong in that 1%. There is a thriving community around r/Medical School Anki; YouTube channels like Med School Insiders, Ali Abdaal, The AnKing. This doctor has an “unusal route” to achieve exceptional academic results. I was a mediocre K–12 student but graduated #1 in my medical school class:

I’m sure that many of them would tell you that they needed to attend the lectures and take their own set of notes to facilitate their learning. But I call B.S. I skipped almost every lecture and yet achieved the number one score on every exam.

You may not agree with the above statements. What I want to point out from all these sources and testimonies is that, superficially, if medical school students are using Anki to learn, and if you’re not, you’re missing out.

You don’t have to believe me. I’m not the only one writing about the science of learning. Unfortunately they’re buried deep under the field of educational/cognitive psychology. You can check out How to Learn About Meta-Learning: My Resource List or visit Gwern’s Spaced Repetition for Efficient Learning to discover for yourself.

Closing Remarks: Part I

1. We’re never taught how to learn (correctly/effectively/efficiently) in school.

You need to:

I. unlearn the wrong ideas about how to learn

II. uproot old learning habits and methods

2. Established yet wrong ideas about how to learn prevent you from achieving your full potential.

For the second part, please see Why 99% People Never Learned How To Learn And How to Become That 1% (II)